Chapter Two -- Literature Review

2.0 Introduction

In today’s market place organisations are constantly having to deal with the demands for change internally as well as externally, furthermore, how organisations adapt to these changes and overcome the obstacles can define how successful they are in the short and long term (Oakland & Tanner, 2007; Smith, 2005; Walker, Armenakis & Bernerth, 2007). Although, there is a common tendency in organisations to implement change and its growing literature, still many organisational change efforts fail, moreover it can be argued that an organisation’s long-term survival may depend on its ability to manage resistance to change (Beer & Nohria, 2000; Elving, 2005; Murphy, 2002). The purpose of this chapter is to critically analyse how to effectively manage the internal change processes in conjunction with the effects of organisational change on employees’. Moreover, as this paper contains a change context, it is important to gain a comprehensive perceptive and understanding of the subject matter. Firstly, a discussion will lead from defining change, as well as exploring the factors influencing change, and the resistance to change and finally how change can be effectively managed before coming to a viable conclusion.

2.1 Change Defined

It is understood that change is becoming increasingly frequent in the business environment, and is considered as a critical factor of effective management (Hussey, 2000). According to Smith (2005), change can be formulated as the method of shifting to a new state; one in which differs from the existing state. However, there may be many barriers for organisations to readily and successfully change. Vakola (2004) postulates that as an organisation endeavour to survive and maintain a competitive edge, it is apparent that they are re-engineering, reorganising, and downsizing, as well as employing new technology. This emphasises that organisations are constantly trying to change, which may not only place an organisation under much strain, but as well as individuals. Hannan and Freeman’s (1984) structural inertia theory disputed this assertion illustrating the inflexible nature of organisations where organisational change can be both complex and harmful. Additionally, Smith (2005) attested to the fact that change in an organisation can be dynamic enough to be internal or external, as well as being unpredictable enough to be planned or unplanned. Consequently, it can be argued that change does not always proceed accordingly to as planned; there are many factors that may influence change in an organisation.

2.2 Factors Influencing Change

Several researchers have highlighted that change efforts are influenced by internal and external factors (Hoag, Ritschard & Cooper, 2002; Oakland & Tanner; 2007; Walker, Armenakis & Bernerth, 2007). Weick and Quinn (1999) assume external factors as changes in technological demands or internal factors such as in key personnel. Furthermore, Armenakis et al (2007, p. 761) suggests that the change efforts are influenced by; “content, contextual, and process issues as well as the individual differences that exist among the change target”. Consequently, Oakland and Tanner (2007) emphasises the role internal drivers have in manifesting external drivers in the process of change. Accordingly, Davidson (2002) claims that resistance to change may be ego related if imposed externally as opposed to internally.Moreover, with planned and unplanned changes there are significant external and internal factors causing pressures within an organisation; these will be discussed below.

2.2.1 External Forces

Accordingly, Trader-Leigh (2001) and Armenakis et al (2007) postulates the key resistant factors to change, one argument was the political factors such as government legislation, regulations and policies; this is an external force of change. Changes in government and new policies impose constraints; whereby organisations must comply and adapt to the new strategies (Trader-Leigh, 2001). Therefore, Lindblom (1994) argues that an organisation must engage in a political struggle if a change is required, and further emphasises that no important changes come without it.Additionally, Beugelsdijk, Slangen and Herpen (2002) acknowledge market competition to be another influence of external force on organisational change. Armenakis et al (2007) advocates competitive pressures as external contextual issues, and further suggests that organisations have little control over these forces, thus, organisations must make appropriate changes in response to such demands. Thurlby (1998) and Beugelsdijk et al (2002) similarly argue that due to changes in competitors’ prices and products, organisations have to make suitable changes in response to the demands from the competition they face in the market. Consequently, Collins (2001) and Vollman (1996) also suggest that organisations that fail to adapt or respond to such changes in time may face the risk of losing market share to competitors.

Another external pressure in today’s organisations are the social factors, which has been an increasing common external force of change (Kim & Hung-Ng, 2008). Consequently, Murkherji and Mukherji (1998) argue that social change occurs due to conflict caused by differential values within cultures and societies that results in fluctuations in demand for products. Furthermore, Chelsom (1998) outlines the technological factors influencing organisational change, and further postulates it can lead to major changes for an organisation to maintain its strategic position. In contrast, Cooke (2002) hypothesises that development’s in technology manifest change in relation to the Human Resources who seek innovative ways of doing practically identical things.

2.2.2 Internal Forces

It is understood that the process issues refer to the actions undertaken in organisations during the introduction and implementation of the change. (Armenakis et al, 2007). Therefore, organisational change must be communicated readily to individuals within an organisation (Armenakis, Harris & Mossholder, 1993). Similarly, Smith (2006) assumes readiness in organisational change is essential, at both individual and organisation level, in order to prepare individuals for the proposed change. In addition, it can be argued that individual differences in organisations play a major role in influencing organisational change (Armenakis et al, 2007). Consequently, Smith (2005) outlines the people side of organisational change, and highlights that people are a vehicle for change, and further debates that people can also be an obstacle to change. Similarly, Patterson, West, Lawthom and Nickell (1997) hypothesises individuals are considered as a primary factor in organisational change. Nevertheless, it is the people who do the work of organisations that the ability to achieve the organisational change is determined by the attitude of the employees (Smith, 2005).

2.3 Resistance to Change

There is an argument that resistance to change is a core topic in change management and should be considered to achieve organisational change readily (Val & Fuentes, 2003). According to Smith (2006) and Ansoff (1990) resistance to change can be seen as a major barrier that organisations face. Ansoff (1990) further highlights that resistance can have a major affect on organisational change by delaying the process, obstructing its implementation and increasing its costs. It can be further argued that resistance to change pioneers expenses, as well as a hindrance into the change process (Lorenzo, 2000). Similarly, Kotter (1995) argues that resistance is an impediment in the organisations design or structure preventing change. However, Hoag, Ritschard and Cooper (2002) oppose that view and suggest while such aspects can influence the change process, they cannot be considered as “obstacles”.Research highlights that change resistance has become an increasingly expected constituent in any organisational change process, and to some extent considered as a natural form (Smith, 2006). On one hand, Geisler (2001) illustrates that change resistance is acknowledged to be a significant threat affecting the successful running of strategic initiatives. On the other hand, resistance has also been considered as a source of information, as some perceive resistance as being useful in learning how to develop a better understanding and achieving a successful change process (Beer & Eisenstat, 1996; Piderit, 2000). In addition, Val and Fuentes (2003) recommend the fundamental sources of resistance as the perception of change, as well as low motivation for change and lack of creativeness when selecting appropriate change strategies. Moreover, such resistance could highlight the aspects that are not seriously considered in the change process, in order for change managers to undertake appropriate action (Waddell & Sohal, 1998).

It is generally accepted that individuals endure a reaction process with the confrontation of change (Bovey & Hede, 2001; Jacobs, 1995; Kyle, 1993). Similarly, Val and Fuentes (2003) propose that resistance to change is related to the difficulties created by deep rooted values such as cultural and political elements during the change process, along with the departmental politics and deficiencies in the required capabilities. Consequently, numerous literature reviews on resistance reveals that individuals and groups can react to change in different ways, as change can cause fear and a sense of loss of the familiar (Barnes, 1995; Morris & Raben, 1995; Smith, 2005). Similarly, according to Thomson (1990) resistance to change can occur from (a) fear of failure; (b) threats to status; (c) lack of information; and (d) lack of perceived benefits. In addition, resistance may also occur when individuals have past resentments toward a leading change (Block, 1993; Elving, 2005; O’Toole, 1995).

In contrast, King and Anderson (1995) is equivocal in noting the role played by previous indifferent experiences of change by individuals, who react negatively synthesised by a resistance to change from their normal working condition and ambience. Certainly, it may take some time for employees to understand change in an organisation and commit to the change (Armenakis et al, 1999). Therefore, due to the range of human responses to change, it holds barriers for organisations to successfully and readily achieve the change (Kotter, 2002). In fact, “altering the work setting is a potent lever for inducing change in member behaviour” Elving (2005, p. 131). However, Vakola (2004) suggests that employees’ response to change may vary from positive to negative, and can be received with excitement and happiness or anger and fear. Similarly, Smith (2005) and Scott and Jaffe (1988) argue that change for some is perceived as exciting and stimulating as they cannot wait to get to the new state of things, however, for others change can be deeply unsettling, and can be perceived to be a major threat to the individuals values, and something to be resisted at all times.

H1. Negative attitudes towards organisational change will positively relate to previous bad experiences of change.

Additionally, individuals may resist to organisational change due to uncertainty and job insecurity, this is commonly about the aim, process and the expected outcomes of the change (Buono & Bowditch, 1993). Conversely, individuals may simply resist change because they are anxious about their own personal failure (Mink, 1992). It is often found that uncertainty may result in an increase in informal communication leading to rumours within an organisation (Smith, 2006). Similarly, uncertainty can create negative attitudes in conjunction with organisational change leading to insignificant effects such as stress, low commitment and reduced job satisfaction and trust (Schweiger & DeNisi, 1991; Tsang & Kang, 2008). Moreover, Elving (2005) hypothesises that individuals that face uncertainty and job insecurity assume that the proposed change will be a threat to their job, whether that the individual will still have the job after the change, as well as having the same co-workers, and whether the individuals are able to perform the tasks in the same way as before. Despite this, resistance could also extend to the individuals personal life, in which it can extend to the work environment leading them less willing to sustain the change, as they are more focus with issues in their personal life (Palmer, Dunford & Akin, 2006).

H2. Employee uncertainty in an organisation will negatively affect the readiness for change.

Consequently, there has been increasing controversy over change managers neglecting the important human dimension when following the implementation of organisational change (Bovey and Hede, 2001; Levine, 1997). A longitudinal study conducted by Waldersee and Griffiths (1997) that consisted of a large number of Australian organisations outlined how effectively the resistance phase is managed when implementing change (Bovey and Hede, 2001). Similarly, Miyashiro (1996) places emphasis on change agents communicating the change effectively to individuals within the organisation. Furthermore, Lorenzo (2000) discusses that if an organisation has gone through a number of changes, some may resent to another change occurring. Subsequently, Self (2007) suggests that managers may be curious why they have not attained expected results from the previous change, resulting in cynical individuals, as well as frustrated managers strongly believing that the failure is due to the individuals resenting to change. Pederit (2000) similarly assumes that if external factors are not a consequence of change failures, then it must be considered the fault of individuals within an organisation resenting to change. In contrast, Miyashiro (1996) postulates this is due to the failure of management to successfully create and manage readiness.

H3. Disregarding the human element and dynamic in organisational change can have an adverse effect on the change proposition and employees.

2.4 Managing Resistance and Change

From previous discussion on resistance to change it can be argued that an effective organisational change is accomplished by “people”, this stresses the importance in the effectiveness of managing organisational change, that is, recognising the responses and reactions to change (Armenakis et al, 2007; Smith, 2005). Similarly, Smith (2006) discusses that people are an essential factor in achieving change; hence managing change within the culture of an organisation is fundamental. Conversely, it can be argued that financial pressures may be associated with achieving this (Oakland & Tanner, 2007). However, it must be stressed that understanding employee responses to change can aid management and achieve the objective of employee commitment to change (Armenakis et al, 2007). Consequently, enabling employees to participate in the change process is acknowledged as an admired strategy to avoid resistance to change (Chirico & Salvato, 2008). Greasley et al (2008) acknowledges that employees will desire becoming empowered in their role within an organisation; in effect they can resist a new idea if it compromises their role even if the idea sounds progressive enough to have a positive impact. Additionally, learning such as training and development programs is another essential factor (Hert, 1994). For instance, the involvement of external consultants can be extremely beneficial for an organisation, as they are able to provide industry expertise, skilled resources, as well as change management knowledge and experience (Oakland and Tanner, 2007).Certainly, organisational change is perceived to be extremely difficult by many (Staniforth, 1996). Beer and Nohria (2000) cited that 70 per cent of change approaches are unsuccessful due to the deficiency in the strategy and a lack of communication and trust, as well as lack of top management skills and resistance to change. Similarly, Gravenhorst, Werkman and Boonstra (1999) agree a similar view that over half of many organisational change processes fail, and are unable to reach the anticipated results. Consequently, Smith (2006) recommends that trouble-shooting is an important factor during change implementation; instead of losing confidence, the obstacles and setbacks should be openly acknowledged and considered to primarily learn from experience. However, often, organisations implement change without any type of plan or communication to the individuals affected by the change; this is a major cause acting as a barrier to a successful change process (Chirico & Salvato, 2008).

Conversely, Crowther and Murphy (2002) advocates that organisational change programmes may fail because of lack of employee participation and decentralised management. Subsequently, by creating readiness before attempting to make the change in an organisation can largely avoid the need for later action to cope with resistance to change (Smith, 2005). Consequently, Elving (2005) suggest that when employees are having to change, low level of resistance to change within the organisation must exist, in order to achieve a successful change effort. Similarly, McCallum, Vasconcelos and Norman (2008) assume that the attempt to influence people in organisations may comprise of a structured interaction, this may include collaborative decision-making, delegation and the presence of pre-established relationships.

H4. Employees will be more inclined positively towards the implementation of organisational change if there are high levels of organisational responsibility and participation imposed on them.

Moreover, it can be argued that communication is imperative to the successful implementation of a change program, which can prove to facilitate the change process through preparing people for change (Klein, 1996). However, Moran and Brightman (2001) states that adjustment time is also vital to facilitate the change process. A study conducted in a public sector organisation by Proctor and Doukakis (2003) indicated that poor communication resulted in negative feelings among the employees, as information was acknowledged through the rumour mill and local newspapers. Indeed, when change is not communicated effectively to individuals affected by the change in the organisation, it is evident that resistance becomes a huge problem (Smith, 2006). Consequently, Elving (2005) postulates the principle of change communication, which should primarily be to inform individuals about the proposed change and possible alterations that may affect their job role. Furthermore, Elving (2005, p.131) cited Francis (1989) which highlights the two objectives of organisational communication, firstly, employees must be informed about such policies and tasks, as well as organisational issues, and secondly the “communication with the intention to create community within the organisation”. In the same way, Waddock (1999) assumes a similar view of creating a community spirit within an organisation, and an emphasises on developing a community in an organisation, which is trust, caring, and belonging, working with others, making a contribution, and allowing individuals to co-exist in an organisation. Jones and George (1998) postulates that trust leads to distinctive affects such as higher levels of collaboration leading to positive attitudes and greater levels of performance. Subsequently, one can argue that the change effort is very much dependent on the organisation to change the individual behaviour (Elving, 2005). Similarly, Goodman and Dean (1982) justify that organisation can only change when the member behaviour changes, as the members’ are dependent on the functioning of the organisation.

H5. Low levels of organisational communication will positively relate to low levels of commitment and trust within the organisation affecting the readiness for change.

Additionally, there is rapid growth of literature about organisational change and how it can be implemented in order to achieve successful change in organisations; Lewin (1951) provided a classic model of change theory, which consists of three-step change model; unfreezing, transitioning, and refreezing. The unfreezing step was described as an imperative phase in organisational change in which it is considered an essential first step in accomplishing change. Kritsonis (2004; 2005) argues a similar view that the ‘unfreezing stage’ is compulsory to overcome individuals’ resistance to change and group conformity. According to Lewin (1951) the first step was achieved by “deliberate emotional stir up in order to break open the shell of complacency and self-righteousness in organisations”. (Lewin 1951, p. 229). In comparison, Kritsonis (2004; 2005) suggests the attributes that support the unfreezing step; these include, motivating individuals through the preparation of change, recognising the need to change, as well as participating in reorganising exertion along with building trust.

In comparison, although Lewin’s model is considered as the pioneer in the understanding and the evaluation of organisational change, the model has been criticised by many for being too simplistic. Burnes (2004) criticised Lewin’s change model and argues that it is only relevant to small-scale changes in firm conditions, and further debates for ignoring issues such as organisational politics and conflict. Similarly, Orlikowski & Hofman (1997) debate that Lewin’s model perceives change as a distinct event to be managed over a limited period, and further illustrates that the model has become less appropriate due to unsteady and uncertain organisational and environmental conditions. Burnes (1996) agrees that a number of elements have changed since Lewin’s theory was originally presented, and there have been major developments in understanding of change management since Lewin’s model. On the other hand the model is yet extremely relevant as many modern change models are based on Lewin’s model, which is still used in practice (Armenakis et al, 2007; Counsell, Tennant & Neailey, 2005; Smith, 2005).

2.5 Research Model

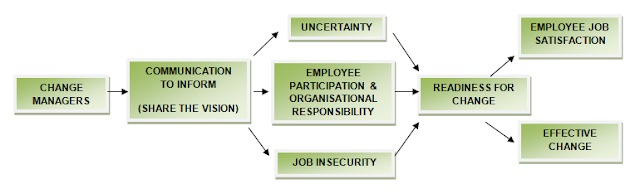

The proposed hypotheses lead to a research model of the functioning of change managers’ measures in conjunction with the effects of organisational change of employees (see Figure 1). The hypotheses attained from this chapter emphasise employee attitudes and perception towards organisational change, which have an influence on readiness for change.Figure 1: Conceptual model of change managers’ communication during the implementation of organisational change.

|

| Model of Organisational Change |

2.6 Conclusion

The literature highlights that organisational change has become a frequent imperative in the business environment (Hussey, 2000; Smith, 2006). After reviewing the various arguments relating to the driving force of organisational change, a number of factors have to be taken into consideration for change to be implemented in the way in which best suits the organisation, for instance, not all employees will be receptive to the notion of having to operate in a different way and will obviously want to safeguard their interest as much as the organisations interest (Ansoff, 1990; Elving, 2005; Smith, 2005). Therefore, reading between the lines, change can be effectively managed by streamlining all the internal and external forces in a way in which ensures that change will be communicated readily to employees (Armenakis et al, 1993; Oakland & Tanner, 2007).It goes without saying however, that is easier said than done with the resistance to change an ever present barrier and the ability to facilitate and initiate change can often lead organisations down hazardous routes. Indeed, Geisler (2001) and Beer and Nohria (2000) attests to this belief that initiating change can be difficult with many organisational change programs failing due to resistance to change and poor management. Consequently, allowing people in organisations to participate in the change process, as well as training and development programs, and effective communication from change agents can prove to facilitate a change process through preparing people for change (Chirico & Salvato, 2008; Klein, 1996; Murphy, 2002; Oakland & Tanner, 2007). Furthermore, the literature review in this chapter highlights that such resistance to change can highlight the aspects that are not seriously considered in the change process, in order for change managers to undertake appropriate action, and develop a better understanding (Beer & Eisenstat, 1996; Piderit, 2000; Waddell & Sohal, 1998).

The aim of this research is to understand the importance in the role of management in implementing effective change, and combating resistance to change.

To counter that argument, a methodology discovers the research question: “What are the effects of organisational change on employees and the role of the manager?” in practice. The next chapter considers the appropriate approaches to achieve the aims of the study.

No comments:

Post a Comment